by Rachel Lee Davis, with Dr. Peter Bream, Jr., MD FSIR

The Fight for Water

Water is fundamental to human life. We are taught this in schools and in our homes, we experience this when we are thirsty. Some understand this because of their geography and access to wells or the precious subsurface reservoirs of water trapped by desert plants and strange animals. Patients with Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes and symptomatic hypermobility spectrum disorders understand this too, though our experience is somewhat different.

Dysautonomia, for as yet unknown reasons, though autoimmune disorder is a rising suspect, prevents EDS patients from properly retaining water. Our bodies do not store it as long as a typical body, flushing it out with urinary frequency that can begin in early childhood as adult patients and parents of suspected and diagnosed EDS kids often report. Increasing sodium levels and water is the first intervention. Products like Liquid I.V. drinks and SaltStick support these efforts, while others go with old fashioned salt tablets or simply drinking a couple teaspoons of Himalayan salt in a large cup of water every day. The effort to increase water is a daily chore. While most people can do their 8 cups a day or whatever amount mathematically coordinates weight to desired water intake, we must drink nearly double that amount.

Without contrasting experience, we often live for years not knowing what it really feels like to be hydrated. Our bodies compensate, as does the mind. But as dysautonomia advances, a general dysfunction in the peripheral nervous system characterized by heat intolerance, elevated heart rate, frequent urination, and dizziness to name a few takes on more severe spikes in heart rate, drops in blood pressure, and begins to destabilize the mast cells of the body which are vital to proper immune function…we miss water even more. We call it brain fog, for lack of a better term. Your mind is still functioning but with a lack of efficiency and accuracy you are aware of yet unable to compensate for. The body is low on energy, exhausted from drops of blood pressure and nearly passing out or completely fainting as the natural safety mechanisms of our complex system attempt to return blood flow to the brain by making us lay down.

Water conducts electricity. The minerals we absorb from it and our food help regulate the polarity of our neurons so that they can send vital signals to the rest of the body and back again. Water flows through tiny, microscopic tubes of elastin and collagen called fascia, that coats every major internal structure in the body and is larger and more malleable than skin. It can even anticipate movement, communicating in a breadth of a second with that part of your brain that knows you will pick up a cup even before you yourself are aware of it. What else happens when these systems and organs are not full to the brim with the essential nutrients and fluids they require? And yet, for some of us, no matter how much we drink it will never be enough.

What can we do?

On the spectrum of EDS/HSD patients who need intravenous fluids semi-regularly to daily, there are those who can survive with liquid I.V. drinks, those who need an infusion during emergencies, those who need weekly drips and then those who, due to other co-complications that become quite advanced at this stage, cannot eat or drink by mouth at all. For the patients on the latter end of this spectrum, a whole new set of problems can arise. Connective tissue disorders affect blood veins and vessels. Indeed, they affect the entire body! Vascular Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, one of 13 types, is best known for life threatening complications in the circulatory system. This is in the form of aneurysms and other abnormalities of the blood vessel wall. But many professionals do not realize that anyone with this category of connective tissue disorder can be affected. The veins are more fragile, subject to tearing and excessive scarring that, if mismanaged by nurses, doctors, and vascular access specialists over the years, can permanently cripple a patient’s ability to have blood drawn or receive fluids, medication and nutrients through the typical access points. Dr. Peter Bream, Jr., MD FSIR, is a Professor of Radiology at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill who has a passion for venous access issues. He has begun to tackle this unique issue in the EDS/HSD community.

Soon after arriving at UNC from Vanderbilt University, Dr. Bream began seeing POTS patients for procedures to place PICC lines, ports and other catheters. It wasn’t long before he discovered that many of these patients had something more in common than dysautonomia: Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. During my first phone call with him, Dr. Bream expressed professional frustration with how some of his new patients had been mismanaged. Some had been given the wrong equipment for their treatment needs resulting in loss of access, terrible infections, and ultimately even more suffering than they started with. A typical patient would get a device that was not meant for continuous access which would lead to an infection. To make matters worse, once the infection was discovered, the device would be removed and replaced with a new one on the other side. This could happen 3, 4 or more times! Pretty soon, the veins for access would be used up and Dr. Bream would have to resort to more invasive procedures such as stents and balloon angioplasty to maintain the lines.

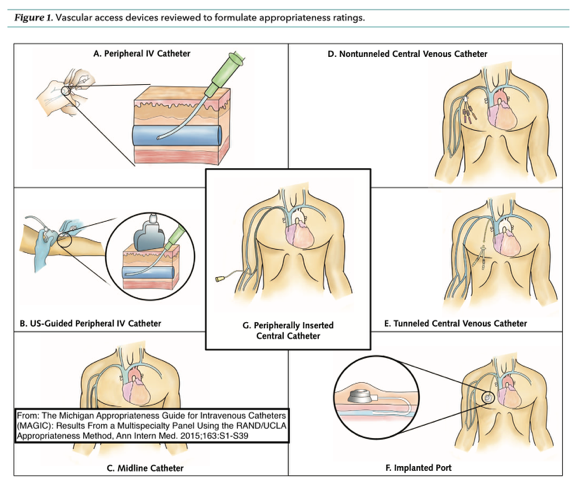

My response to this was very empathetic. As both patient and advocate, I’m desperately hoping to NOT end up in such dire straits, but I also know that much of my health depends on the infusion treatments I was receiving before it became clear that my own veins could not handle the typical temporary IV catheters. “These issues could be prevented,” Dr. Bream said, and told me about the process he hoped to implement for his EDS/HSD patients, the three types of venous access equipment, and how they should be used. (Figure 1)

- PICC – peripherally inserted central catheter (G in the diagram). This device typically goes into a vein in the upper left or right arm. The vein is found via ultrasound on the day of the procedure, and a 30-40 cm (approximately) polyurethane catheter is inserted into the superior vena cava of the heart, via the peripheral vein. This is done under local anesthesia. The lumens, the dangly bits that hang down outside the body and hook up to the IV drip or other equipment, provide a safe way for fluids to go in or out without introducing bacteria into the body. As long as they are flushed properly with every use, a PICC can be used frequently for about 18 months, making it the simplest mid-term or short term access option (if a bit awkward and uncomfortable at times). It has a low, but significant infection rate.

- Tunneled Cuffed Venous Catheter (Tunneled CVC, E in the diagram). This is a central venous catheter typically placed in a neck vein and then routed under the skin to come out on the chest wall. The fact that it is routed under the skin gives it extra protection that a PICC line does not, and is ideal for patients who need daily or even continuous infusions. If cared for properly, these catheters can remain in place for years.

- A Port – or totally implanted venous access device (F in the diagram). Ports can be single or dual lumen catheters that enter the neck or shoulder vein, but are placed completely under the skin on the chest wall or arm. They are designed for patients needing infrequent access. The port has a silicone diaphragm that is punctured through the skin using a special, non-coring needle called a Huber needle. The number one problem Dr. Bream sees with patients referred for access is that they have had a port placed for daily infusions. Ports are not indicated for access, meaning that they are not designed, for more than two times a week. When they are accessed continuously for weeks at a time, the needle can cause erosion of the fragile skin and does not have the protective measures of a cuff and a tunnel to fight off infection. Bacterial on the skin can crawl down the needle and into the port and directly into the bloodstream. The stiff needle also causes excessive wear and tear on the tissues. Of all venous access devices, they have the lowest overall infection rate, but that depends upon the fact they are only intermittently used. Ports can stay in a patient for years if they need to and don’t get infected.

For EDS patients, the risk and consequence of infection can trigger a system wide flare and significant progression of symptoms through the resulting illness. Therefore Dr. Bream takes a personalized approach to each patient. If a patient is starting therapy, the plan of care typically begins with the placement of a PICC, so that the patient can work with their cardiologist and primary care physician for a few months to determine how often and how long access is needed. From there it is a simple procedure to remove the PICC line, and the patient can be scheduled for the placement of a port or tunneled CVC based on actual need. The basic tenet is that a patient should have the smallest line with the least number of lumens to get the job done. The line should also be removed if it is not being used. So, while this process may be time consuming and emotionally challenging, it can preserve venous access and prevent the serious complications that could have life-long effects in the EDS/HSD spectrum of disorders.

Q&A

Why do some doctors place lines that are not the proper indication? That is, not the right tool for the job at hand?

Most physicians who place lines specialize in that and are not primary caregivers. If there is not clear communication regarding the intended use of the catheter, then the wrong catheter can be placed. Unfortunately, many physicians placing lines simply follow the order of the primary care physician and don’t inquire about the line’s usage. Dr. Bream makes sure his trainees fully understand the proper use of these devices.

If you are considering a catheter, or have a question about your catheter, don’t wait to get help. Research what this type of equipment is used for and how it is meant to be cared for. Communicate regularly with your physicians about potential complications and concerns, or simple monthly status reports so that if a problem does arise there is context and clarity about your case. A well-chosen, well-placed catheter used appropriately can be life changing for Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome and Hypermobility Spectrum Disorder patients. Water is life.

My 40 year old daughter has eds 3 n has severe migraines to where she doesn’t want to live does diet n vitamin management seriously help n Xtra fluids? Please help me we are desperate life n death

I am excited as I think this article has solved the reason why I a major medical problem that I’ve have had since a child & at 73yo still have, I also have Ehlers Danlos, I also have Neuromuscular Junction Impearment, My situation at present with dehydration it is a very serious especially as I’m having problems staying hydrated due constantly trying to manage the signal problems eg as soon as I drink within a very short period I loose Most of what I’ve drunk etc

Found this article doing some low-key research into my own struggles with staying hydrated w/ POTS & EDS… no matter how much electrolytes I drink, it’s not working. Starting IV fluids 2xweek soon, and I’m terrified. Thanks for helping me feel less alone, and for the information – empowering and reassuring to get some details!